Two converging paths united

in a singular mission for justice

June 23, 1952

Korea

Crouched low with weapon ready, Private James Brown led the diamond formation past rice paddies and through the low grassland of South Korea. Based on a military map, he was forging the uneven terrain of “Hill 207,” and he and the rest of the almost 40 soldiers in his platoon had crossed the line of demarcation into the neutral zone. A few minutes past 3 a.m., the 19-year-old, who had only been near the front line for three months, squinted through the pitch-black night searching for any hint that the enemy was close.

Without warning, mortar fire burst through the darkness. The men on patrol beside Brown fired flares in the direction of the enemy. No one could see the attackers, but the streaks of their tracer bullets whizzing by gave them away. Suddenly, a blast of pain exploded in Brown’s right side. A grenade. Shrapnel sprayed into his arm and leg as gunpowder enveloped him. Brown fell to the ground and continued to return fire until a voice yelled, “Pull back!” Brown struggled to his feet and limped back to the line, where a medic bandaged his wounds, administered a shot of morphine and waved over a stretcher.

Summer 2002

North Carolina

As soon as her fingertips hit the wall, Eleanor “Ellie” Morales (JD ’10) looked at the scoreboard. The numbers confirmed it. She won the North Carolina 3A state championship in the 500-yard freestyle. The hours of practice and intense training had paid off — and not just in this victory for her Hickory High School swim team. Her work ethic, drive and success had captured the attention of three branches of the U.S. military.

“Soldier” and “sailor” had not made the list of answers when Morales considered what she wanted to be when she grew up — at least not until her senior year of high school when the 17-year-old was offered admission to West Point and the Naval Academy. It seemed her lifestyle, personality and penchant for serving fit well with the discipline and team environment found in the military. Ultimately, she was awarded and accepted an Army ROTC scholarship to Davidson College, where she continued her swimming career. When she graduated college, she was commissioned into the Army as a second lieutenant.

July 1952

Osaka, Japan

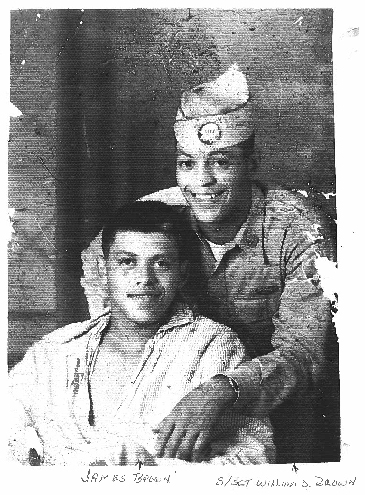

Brown looked up from his hospital bed and saw his brother, William, a fellow Army soldier stationed in Japan with the 187th Airborne Infantry Regiment. After receiving news that James had been injured, the older Brown made it to the hospital in Osaka as soon as he could. Taking in one another, they knew they were far from where they started.

James and William grew up in Newport News, Virginia, during the Great Depression. After their father died when James was 3 years old and their mother remarried and moved away, James and his five siblings were raised by their grandmother. It is no stretch to say that they knew poverty.

“We had no indoor plumbing, no water or gas lines,” James remembers. “I had to pump water into our kitchen to get clean water. It was not an easy life. We never had money, but we were always fed.”

James walked more than 3 miles each way to school every day; there wasn’t money for the streetcar. He started working when he was just 9 years old — first selling newspapers and then cleaning a dentist’s office for a quarter. When he was 13, he woke up at 4 a.m. to make deliveries for Peninsula Dairy before the milk truck driver dropped him off at school. After he finished ninth grade, supporting his family superseded scholarly pursuits, and he left school to find work.

In June 1950, when James was 17, the Korean War erupted. The North Koreans, supported by China and the Soviet Union, invaded South Korea in an effort to unite under one system of government. The sudden and aggressive attack drove South Koreans into a small corner at the southeastern tip of the peninsula. Near the point of defeat, South Korea, the U.S. and other allies boldly pushed the North Koreans back onto their soil and nearly into China. But six months into the fighting, the battle returned to South Korea.

For years after that initial and dramatic tug-of-war for land and political power, momentum seesawed across a 150-mile stretch of land along the 38th parallel of the Korean peninsula. Skirmishes and stalemates dominated battle strategy. However, heavy outbursts of artillery fire and periods of increased ground attacks kept the conflict fueled and in demand of more manpower.

The Brown family provided some of that power. James’ two older brothers, one of them William, and a brother-in-law had found great purpose and success in the military — just what James sought too.

“I remember William coming home in his dress uniform, and I wanted to be just like him,” said James. “We were always very close. I always described us as ‘like glue.’ All of my brothers being enlisted in the service inspired me to join the Army, and so I did when I was 17. I had to get special permission to enlist from my mother.”

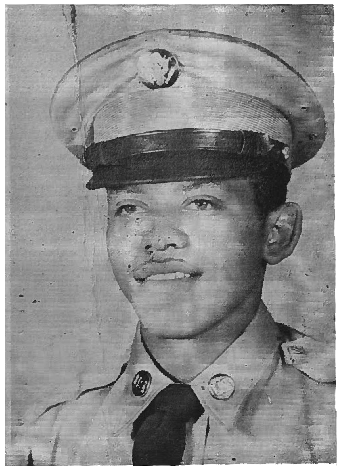

On July 12, 1950, James officially became like his brother. He enlisted in the Army as an infantryman, completed his basic training at Fort Knox and took his first assignment at Fort Campbell. As he had done since he was 9 years old, he supported his family. Each month, James mailed most of his $108.37 paycheck home.

Even as he found purpose and pride in being in the Army, he looked around at his fellow soldiers, aware that President Harry Truman’s 1948 executive order racially integrating the military forces was still struggling to take effect. At the start of the Korean War, most units had not racially integrated. Two years later, progress remained slow.

In March 1952, after driving a truck for the commissary, James received orders that sent him to the front lines of the Korean conflict.

“I was assigned to the 279th Infantry Regiment, 45th Infantry Division,” James said. “This was an Oklahoma National Guard Unit. Here I was, a Black man, suddenly put into an integrated unit that was almost entirely white.”

Once in Korea, James and his company took on a blocking position in the Chorwon Valley, part of the Iron Triangle area, close to the main line of resistance and the major concentration of Chinese and North Korean forces. Skirmishes and stalemates morphed into attacks and assaults, and James and his company quickly advanced to the main line of resistance.

Now, as William stared at his wounded brother, James recounted what he remembered of the night on Hill 207.

After the grenade exploded and a medic came to his aid, James was placed on a stretcher and loaded into the cradle of a helicopter en route to a hospital in Japan. Once there, doctors removed three pieces of shrapnel from his right side — the largest was the size of a quarter, the other two were roughly the size of nickels.

James remained in the hospital for 57 days. Then, on Sept. 8, after he recovered from his combat injuries, James returned to the 45th Infantry Division and joined a new company on the front lines.

Summer 2007

North Carolina

Morales walked through the doors of the Worrell Professional Center on her first day of law school. She had a deferment from the Army to attend law school at Wake Forest, though she served in the Individual Ready Reserve and could get the call to action at any time.

As she was learning the art and science of practicing law, she applied to the Judge Advocate General’s (JAG) Corps. In between semesters at Wake Forest, Morales added to her education through JAG internships — one at Special Operations Command at MacDill Air Force Base and the other in Germany with “Old Ironsides,” the 1st Armored Division.

After graduating from Wake Forest Law in 2010, she trained at the Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School and at Fort Benning before being stationed at Fort Hood in Texas — an assignment she asked for — as a legal assistance attorney representing individual soldiers in legal matters. Six months in, she was hand-selected to be one of the two judge advocates to represent soldiers undergoing the administrative separation process for the base of nearly 40,000 soldiers — a process that managed the cases of soldiers who ran into trouble but not at the level of a court-martial.

“Representing individual soldiers on the defense side started to shape my awareness of the impact of less than honorable discharges,” reflected Morales.

Several months into that work, she flipped sides and took on the assignment of a trial counsel. Within her first week on the job, she and her co-counsel found themselves trying a sexual assault case. For 10 more months, she served as prosecutor.

In 2013, Morales volunteered to deploy to Kabul, Afghanistan, during Operation Enduring Freedom. At the NATO Joint Command base, she was part of a team composed of more than 20 countries. Her responsibility was to advise a Marine Corps general on the law of armed conflict and the rules of engagement — what could and could not preemptively occur on the battlefield.

After her 11-month deployment, during which she earned the Bronze Star Medal, Morales returned to her role as a prosecutor at Fort Hood. Ultimately, she and her husband, Francisco Morales (JD ’11), wanted to return to North Carolina. So she volunteered to join the 82nd Airborne Division — an infantry division based at Fort Bragg specializing in parachute assault operations with the added requirement of being ready to respond to any crisis in the world in remarkably short order.

At nearly 30 years old, she attended Airborne School as one of the few female officers. In those three weeks, she learned how to jump out of a plane at 800 feet and land without breaking any bones. She conquered a night jump, day jumps and jumps with her combat equipment — more than 50 pounds of added weight — and she consistently outpaced the group on routine 5-mile runs. In 2015, after a year of service with the 82nd, Morales transitioned to the Reserve as an Army Captain.

Her service and fight for justice continued when she joined the Department of Justice and worked as an assistant U.S. attorney for multiple districts in North Carolina. Her docket of cases included violent crimes and sex trafficking, efforts for which she received national recognition from the U.S. attorney general. Through it all, she remained an Army soldier.

September 1952

Korea

With his wounds still not yet scarred over, Brown returned to the main line of resistance with a new company of soldiers and was assigned to night watch. The first night in his bunker, he found himself next to a young and inexperienced soldier from South Korea, likely no more than 16 years old. They couldn’t communicate verbally — Brown didn’t speak Korean, and the other soldier knew no English — so they relied on hand gestures and body movement to convey what they needed to. But communication was just the beginning of the challenges.

That first night as Brown scanned his sector of fire, he looked over into the bunker beside him and found it empty. The South Korean soldier had vanished.

“He initially left the position, and I had to get him and bring him back,” remembers Brown.

Finally, back in the bunker, Brown returned to securing his sector. The next time he looked at his fellow soldier, he was shocked again.

“He kept going to sleep, and I could not get him on guard,” said Brown. “Each time I would wake him up to stand guard, he would simply get back into his sleeping bag.”

Night watch required two people — the vast area too much for a single set of eyes. Having a sector unmanned left the line and Brown’s fellow soldiers vulnerable to attack. Knowing firsthand the damage enemy fire could do, Brown felt an urgency to keep vigilant. Yet with the language barrier, he had no easy way to convey to the young soldier beside him the importance of staying awake and alert.

“There was no way that I could man this position by myself, especially at night when we could not see very well,” said Brown. “I was concerned for the safety of myself and my unit.”

After a very anxious first night, Brown alerted his first sergeant, the enlisted leader of his company, of the situation. The first sergeant, equally concerned, took Brown to speak with the company commander — an officer who led four platoons and had the authority to make adjustments. Brown explained the situation, outlining how his fellow soldier’s behavior endangered the entire unit.

“The company commander assured me that they would get an American soldier to replace him, so I went back to the bunker,” explained Brown.

But three days later, nothing changed.

“We went through the same process every night: the Korean soldier would go to sleep, and I was left to scan and guard both his and my security sectors,” said Brown. “So I again spoke to my leadership, as my sleep deprivation, frustration and anxiety were starting to get unbearable.”

Brown alerted various leaders within his unit of the concern three times. The final time, Brown asked his second lieutenant if he could speak to the company commander who had originally assured him that action would be taken. The unit was not under fire, and the commander stood only 200 yards away.

“My second lieutenant ordered me to go back onto the hill,” said Brown. “I told him I couldn’t go back to my position and let our unit remain in danger. He then gave me a direct order, and I reiterated that I would not go back.”

This enraged the second lieutenant, and he threatened to shoot Brown if he did not return to the line. Then Brown turned in the direction of the company commander and walked 15 yards — a total of 18 steps.

“I started to walk back toward the command post where the company commander was located, and the second lieutenant instantly put me under arrest,” remembers Brown. “He told me to put my hands on top of my head, and he pulled his rifle on me and marched me back to the company command post.”

“I should not have refused to follow my superior’s order,” said Brown. “My refusal to do so is a mistake that I still live with 70 years later. It was a mistake that has defined my life.”

Once they arrived at the command post and explained the situation, the company commander’s executive officer — in language filled with racial slurs — ordered “the coward” to the stockade. Brown was immediately placed in pretrial confinement — physically restrained in a small tent, without a weapon, mere yards from the front lines of war. Two weeks later, the executive officer who had barraged Brown with racial slurs charged him with disobedience of a commissioned officer and cowardly conduct before the enemy. For another month, Brown sat in the stockade.

“I should not have refused to follow my superior’s order,” said Brown. “My refusal to do so is a mistake that I still live with 70 years later. It was a mistake that has defined my life. But I was only 19 years old at the time, and I did not consider the lifelong consequences of my actions. When you are in a combat situation, you must depend on the person that is supposed to have your back. I just wanted to speak to our company commander and make him aware of the danger that we were all in.”

On Nov. 14, 1952, in a tent just a few hundred feet from the main line of resistance, Brown pleaded not guilty to the two charges levied against him. The general court-martial, typically reserved for the most serious offenses, lasted less than 30 minutes. Brown was one of the first soldiers ever prosecuted under the new military justice system — the Uniform Code of Military Justice — which still exists today, and the lawyers in his case were still learning the nuances and procedures.

According to the records that exist, Brown was not offered many of the required procedural protections during the 45 days he sat in the stockade. He did not receive access to military defense counsel, a review of the case and charges, or a written report capturing the incident within the required time period after his arrest. He also never had a detention hearing at which he could challenge the necessity of pretrial confinement. Had Brown been tried today, he would have benefited from those many procedural rights not available to him at the time.

The official record of the trial also illustrated the speed of the trial. Neither the government nor the defense asked any questions of the all-officer panel during voir dire. Neither side offered an opening statement. The government presented minimal evidence and only called two witnesses — the second lieutenant who became enraged and a private who overheard part of the conversation. The platoon sergeant who witnessed the entire conversation, the company commander who knew about the situation in the bunker and the Korean soldier who fell asleep were all absent. Brown’s appointed counsel called no witnesses, did not offer any evidence in support of his client, recommended he not testify and advised him to request an officer-only panel, even when one of the charges was disobeying an officer. The transcript of the trial records only a brief mention of the Korean soldier.

“My court-martial proceeding itself was short,” said Brown. “A few parts of it really bother me to this day. I never understood why no one questioned the Korean soldier and why he was only mentioned once at trial. Other than the private who testified, everyone involved in the court- martial proceeding was white. I felt that my side of the story was never really told.”

“I knew that I was not a coward,” said Brown. “I knew that my request to the officers who were in charge could have made a difference.”

After 15 minutes of deliberation, the panel of officers convicted Brown of both charges and moved immediately into the sentencing phase. After a 12-minute hearing, at which Brown offered a brief statement about his life and experiences, the panel deliberated for five minutes. Brown was sentenced to a dishonorable discharge, total forfeiture of pay and confinement of hard labor for five years.

“I knew that I was not a coward,” said the man who still bears scars from enemy shrapnel. “I knew that my request to the officers who were in charge could have made a difference.”

Because of the punitive discharge, Brown’s conviction was automatically appealed. Two years after Brown walked those 18 steps, his cowardly conduct charge was overturned — a fact that Brown would not be informed of for several more years.

After two years behind bars, Brown was released on parole and dishonorably discharged from the Army on April 14, 1954. He moved to Baltimore to be near his family. Even with the dishonorable discharge, Brown got a job at a metal foundry and worked there for 10 years. He got married and had three children. Then he found his second calling as a longshoreman and spent 30 years serving at the Port of Baltimore. For decades, he proved a faithful worker and model citizen, he loved his family, he attended church on a regular basis, and he helped his neighbors. In 2006, after retiring, he moved to North Carolina, where he participates in his local American Legion chapter, serves on his city’s planning board and drives the bus for his church.

Even though he thrived and built a good life, Brown spent decades with a cloud over his name.

Fall 2015

North Carolina

It was a crisp fall day when the Wake Forest School of Law officially launched the Veterans Legal Clinic. It all started because Brandon Heffinger (JD ’14), a former Marine officer who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, wanted to use his Wake Forest education to help solve a problem. Heffinger, who found guidance and assistance from Wake Forest Law Professor Steve Virgil, saw firsthand the challenges his troops and other military members faced as a result of combat trauma. After witnessing the devastation of war, some service members fight a second battle with the effects of trauma, at times including depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and substance abuse.

Federal law outlines a very specific definition for “veteran” based on discharge status. There are five types of discharge characterizations in the military for enlisted personnel: honorable, general, other than honorable, bad conduct and dishonorable. Those with honorable discharges receive a wealth of resources; those with less than honorable discharges often have not obtained legal veteran status and, therefore, cannot access the full swath of benefits.

Nearly 15% of military service members post-9/11 are separated from the military with less than fully honorable status, sometimes because of a misunderstanding of the impact mental health conditions have on behavior or other times because of a discriminating circumstance. While it can be difficult to return to civilian life after serving in the military, a less than honorable discharge compounds the challenges. At times, those who need help the most are barred from receiving it.

Nearly 15% of military service members post-9/11 are separated from the military with less than fully honorable status, sometimes because of a misunderstanding of the impact mental health conditions have on behavior or other times because of a discriminating circumstance.

Over the years, the military has learned more about the effects of war on soldiers and the multiple types of discrimination exhibited in discharges. As a result, Congress has passed statutes, and the Department of Defense has instructed administrative corrections boards to account for the impact of mental health on one’s behavior when allowing service members to petition for retroactive discharge upgrades to obtain legal veteran status to receive full benefits.

While in law school, Heffinger witnessed these changes in the law and monitored how it played out across the country. He imagined that Wake Forest, located in a state that is home to eight active military bases, could assist military service members while offering real-world experience to law students. Service members could receive pro bono representation by law students who could engage in meaningful interaction with clients and gain experience in a legal administrative process — including conducting research, crafting arguments, writing briefs, petitioning a government agency and occasionally participating in a hearing.

After crafting a proposal and receiving the blessing of the faculty, the law school created the Veterans Legal Clinic to represent service members in applying for administrative changes to official records, including discharge upgrades. In the years since its inception, the Veterans Legal Clinic has become a strong piece of a robust and interdisciplinary experiential learning component within the law school, which allows students to practice law in the spirit of Pro Humanitate.

July 2020

North Carolina

Morales waited as the phone rang, hoping someone would pick up the unknown number.

Just a few days earlier, she had walked back through the doors of her alma mater as teacher and director of the Veterans Legal Clinic. Armed with experience, knowledge and enthusiasm, she started sifting through the list of active and potential cases that had come to the clinic’s attention. During her perusal, she stumbled upon an interesting case. It was old. There was little information. It dealt with a dishonorable discharge.

A dishonorable discharge is reserved for the severest of offenses: murder, sexual assault, rape, treason, espionage. It is the worst possible discharge one can have from the military. Receiving a discharge upgrade of one level is rare; to move multiple levels enters the realm of extremely challenging. But Morales has this infectious and unrelenting determination.

“I reviewed the case and was astounded that the service member had endured so many injustices,” said Morales. “I thought it would be a challenging case but a case in which we could make a meaningful difference and provide a great learning experience for the students.”

In the clinic, composed of about eight to 12 students a semester, Morales pairs two law students together to handle two cases. Each student takes the lead on one case and offers support for the other. For most students, these are their first cases. Their first clients.

Military law has its own set of standards and nuances that differ from civilian law. At the beginning of every semester, Morales, who is still in the Army Reserve when not working for Wake Forest, offers her students a crash course in military structure and military criminal law. One key difference between civilian law and the cases Morales and her students petition to military boards of correction revolves around the grounds for relief; one basis is injustice. To make their case successfully, the team must prove that injustice has been done.

Morales also uses her vast network of connections to bring other voices into her classroom. She has invited the director of the Army Board for Correction of Military Records and colleagues from the two other veterans legal clinics in the state, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and North Carolina Central University. Seth Hayden, Ph.D., associate professor of counseling and clinical mental health program coordinator in Wake Forest’s Department of Counseling, also has an academic appointment within the clinic. Hayden works to help students understand trauma and other mental health components they may encounter while working on a case, empowering them to navigate it well in their direct client representation.

In Morales’ classroom, students talk through arguments with their fellow students — some of whom have served in the military themselves. They work together to refine and perfect the strongest arguments for their clients. They point out loopholes and encourage when they identify strengths. It’s a team effort.

As the phone rang again, Morales looked back at the thin case file. This one would require significant research and time to craft an argument. Her optimism said that it would be worth the wait; she hoped her potential client agreed.

“Older cases always speak to me,” Morales said. “Those service members have waited a long time for justice. And there are often more arguments to make because so much time has passed to show what they’ve done after service.”

“Hello?”

“Hello! Is this James Brown?”

And maybe the case spoke to her for another reason. Morales’ grandfathers had served in the military — one in the Army and the other as a Navy dentist — during the time of the Korean War. The folder in her hand held the story of a soldier who fought at the same time.

The phone rang again. This time, a voice on the other end answered.

“Hello?”

“Hello! Is this James Brown?”

May 2022

North Carolina

In July 2020, Brown agreed to let Morales and her law students represent him in a petition to the Army Board for Correction of Military Records. Morales assigned William Crotty (’16, JD ’22) and Ashley Willard (JD ’22) to the case — Crotty as lead and Willard as co-counsel.

She handed them a thin file. Most of the military records had likely been destroyed in a 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center; anything Brown had kept for himself had been ruined in a flood at his home some years back. Nevertheless, the Wake Forest team had two record corrections in mind: prove Brown’s eligibility for combat awards, including the Purple Heart, and upgrade his discharge status four levels — from dishonorable to general.

For a year, Crotty, Willard and Morales pieced together a case. The bulk of their work took place during the height of the pandemic. Crotty connected with Brown nearly once a week, the team consulted with Hayden, and outside collaborators contributed via Zoom calls.

“We needed proof to be able to convince the board of the injustices that led to his discharge,” said Willard, whose two grandfathers served in the Army. “So we talked to an Army historian about where we might find other relevant information. We were looking for context about what it was like to serve in the Army at the time of the Korean War. We reapplied everywhere we could look for information about his case; we asked Mr. Brown directly; we got pictures from him. We were able to piece everything together.”

“This taught me how powerful the law is,” said Crotty. “For Ashley and me – two students that had been in law school for two years – to come in and change something that happened 70 years ago was just incredible. It shows the power attorneys have to make change.”

They submitted a brief and corroborating evidence totaling nearly 800 pages to the Army Board for Correction of Military Records, which outlined arguments of racism and lack of legal protections and counsel offered to Brown at the time of his court-martial. Much of the rationale in the brief originated from military reports and findings published since the 1950s, including the 2018 Wilkie Memo, written by former Secretary of Veterans Affairs Robert L. Wilkie Jr. (’85). The team also collected pertinent evidence to make a case for the Purple Heart.

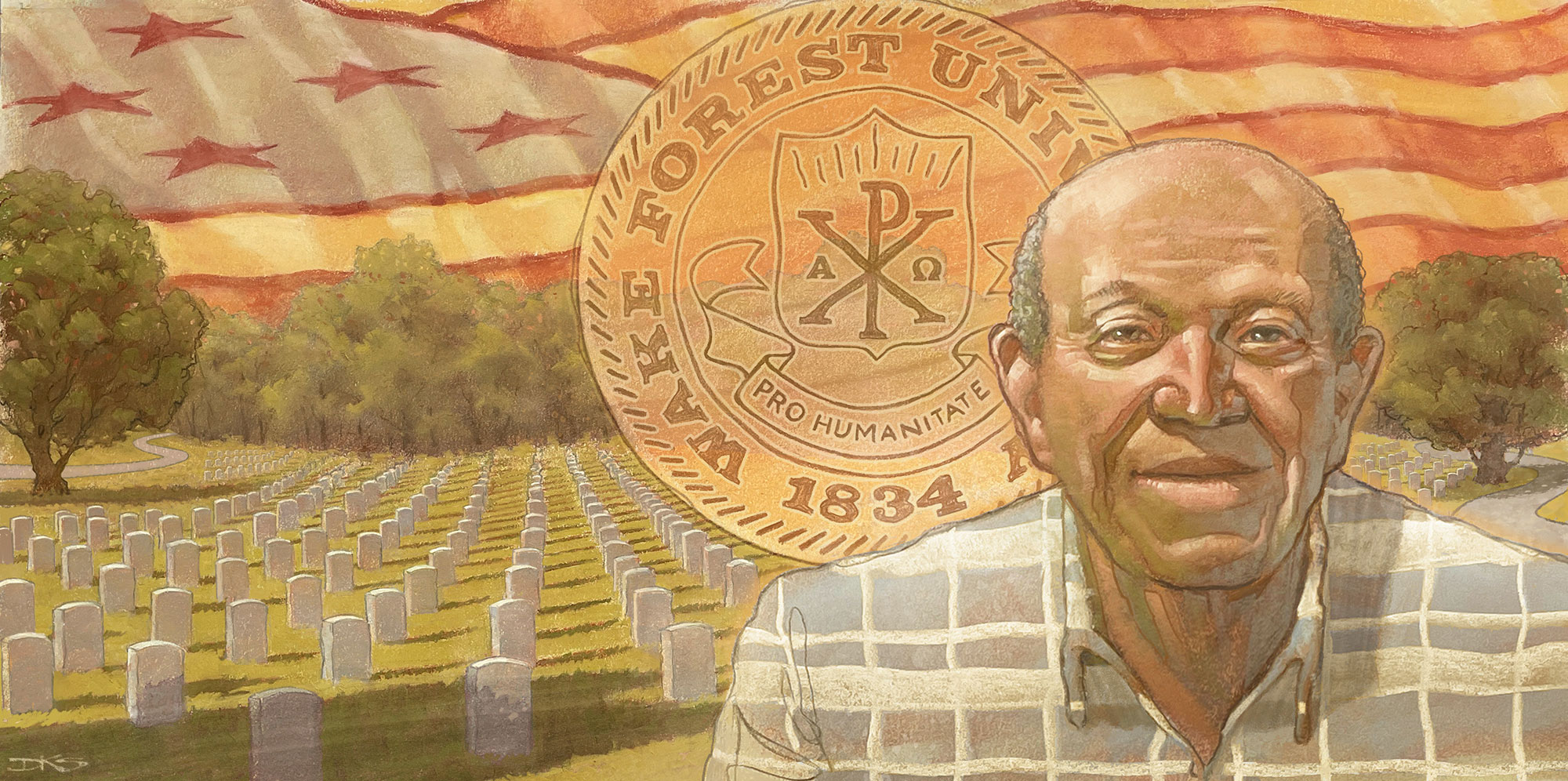

Typically, the Army’s review process takes 18 months. However, because Brown was in his late 80s at the time, the team contacted Senator Thom Tillis’ office to help expedite a decision. Five months after they submitted the brief, and just days before Crotty and Willard graduated with their law degrees, Morales shared the news with her students that the Army Board for Correction of Military Records sided with their appeal, upgrading Brown’s discharge status and awarding him the Combat Infantryman Badge and the Purple Heart.

“This taught me how powerful the law is,” said Crotty, an associate at Garfinkel Immigration Law Firm in Charlotte. “For Ashley and me — two students that had been in law school for two years — to come in and change something that happened 70 years ago was just incredible. It shows the power attorneys have to make change.”

“This case solidified for me that what I want to do in my life is pursue justice,” said Willard, who is now an assistant district attorney in Davidson and Davie counties in North Carolina. “That’s why I came to law school. Spending a year with Mr. Brown and our other clinic client trying to pursue justice for both of them solidified what I want to do with my life.”

At times, the practice of law can feel very technical, but in reality, it is very personal. Even as Wake Forest Law teaches the art and science of law, it also provides opportunities for students to see the humanity of the profession. In many ways, Wake Forest is giving graduates a great gift: the ability to live out Pro Humanitate.

Because of the work of Morales, Crotty and Willard, Brown celebrated his first Veterans Day as a full veteran on Nov. 11, 2022, with his family and legal team at Wake Forest. Since then, neighbors have visited Brown to thank him for serving our country, he was asked to be the grand marshal of his town’s Christmas parade, and people stop him in the store and share their appreciation for his service.

“The biggest thing with Mr. Brown is how humble and gracious he is,” said Crotty. “He’d waited a long time for this and didn’t give up. He was surprisingly patient with us too. We took months to draft this and do it the right way. He was nothing but fully behind us. Mr. Brown would have every reason to be bitter and angry at the military, but he always looked fondly upon his service. He had always intended to make the Army a career.”

“Mr. Brown has changed me not only as a teacher and a lawyer but as a person,” said Morales. “He’s taught me the importance of resilience and perseverance and the humility of knowing that eventually, we’ll get it right.”

“She is my angel,” said Brown of Morales. “There is always a possibility that things that happen to you might be corrected if you persist long enough, if you are determined to ask questions and are blessed enough to have Ellie Morales come into your life. I really, really, really appreciate the work that they all did on my behalf. I believe they did a fantastic job representing me, and I don’t know how I can repay them other than to let them know that I really, really, really appreciate what they’ve done. It is a blessing.”

On Nov. 12, 2022, in front of a crowd of more than 31,000 football fans, Private James H. Brown was awarded a Purple Heart for wounds he received in action on June 23, 1952, during the Korean War. Seven decades removed from the incident that left him with scars down the right side of his body, the near-90-year-old man was finally being honored for the courage he showed as a 19-year-old soldier.

January 2023

North Carolina

On his first official Veterans Day, Brown shared with Morales his dream to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery near his brother-in-law, an Army sergeant major. Morales knew that veterans must have an honorable discharge to be eligible for burial at Arlington. The team had only asked for, and received, a general discharge. Before the day was over, Morales began petitioning on Brown’s behalf again.

Days after Brown’s 90th birthday, Morales picked up the phone once more.

“Mr. Brown, are you sitting down?” Morales asked of her client.

She delivered the news that his discharge status had been upgraded; he had received an honorable discharge. Purple Heart recipient Private James H. Brown is now eligible for a military burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

Even though the teenager wounded in combat a world away was not able to live the majority of his life as a veteran, thanks to a fellow Army soldier and her students, the patriot who loves and honors his country will be forever remembered as one.

Written by Elaine Tooley | Photography by Ken Bennett and Lyndsie Schlink | Illustrations by David Stanley

The Veterans Legal Clinic is supported in part by generous gifts of philanthropy. Learn more about the Veterans Legal Clinic and other robust experiential learning opportunities at the law school, and consider supporting these important and ongoing efforts.

Making the Case: Wake Forest Law Veterans Legal Clinic

The Wake Forest University School of Law Veterans Legal Clinic works on behalf of military service members to petition administrative corrections boards for discharge upgrades to obtain veteran status under the law. One of the most recent cases that Professor Eleanor Morales (JD ’10), director of the Veterans Legal Clinic, and her students took on was that of James Brown, a soldier in the Korean War who was dishonorably discharged.

Honoring James Brown

On Nov. 12, 2022, in front of a crowd of more than 31,000 football fans, Private James H. Brown was awarded a Purple Heart for wounds he received in action on June 23, 1952, during the Korean War. Thanks to the efforts of the Wake Forest University School of Law Veterans Legal Clinic, the near-90-year-old man was finally honored for the courage he showed as a 19-year-old soldier.

Becoming a Good Doctor

Dr. Sarah Rudasill (’17), a second-year surgical resident at Massachusetts General Hospital, is living and empowering Pro Humanitate. Once a Wake Forest student who received the Stamps Leadership Scholarship, the Porter B. Byrum Scholarship and the George Washington Greene Memorial Scholarship, now she is paying it forward for others.