The call of Pro Humanitate – to be a catalyst for good in society – means being willing to enter some of the darkest corners of humanity. Confronting complex issues and working to create solutions to complicated problems implies an element of messiness. Perhaps that is why courage accompanies the curiosity of Wake Foresters. It is not easy to pursue the good when encountering the bad is inevitable. But it is worth it. This story is ultimately about the good, but it will take a meandering path through the dark and disturbing before it gets there.

Many business professionals spend their energy ensuring companies and industries thrive. They conjure up new ideas and pursue innovative avenues. They plumb the depths of risk assessment measures and pore over methods to elevate return on investment. Not many are interested in thwarting the success of a business or understanding it well enough to break it. But, not many are Stacie Petter.

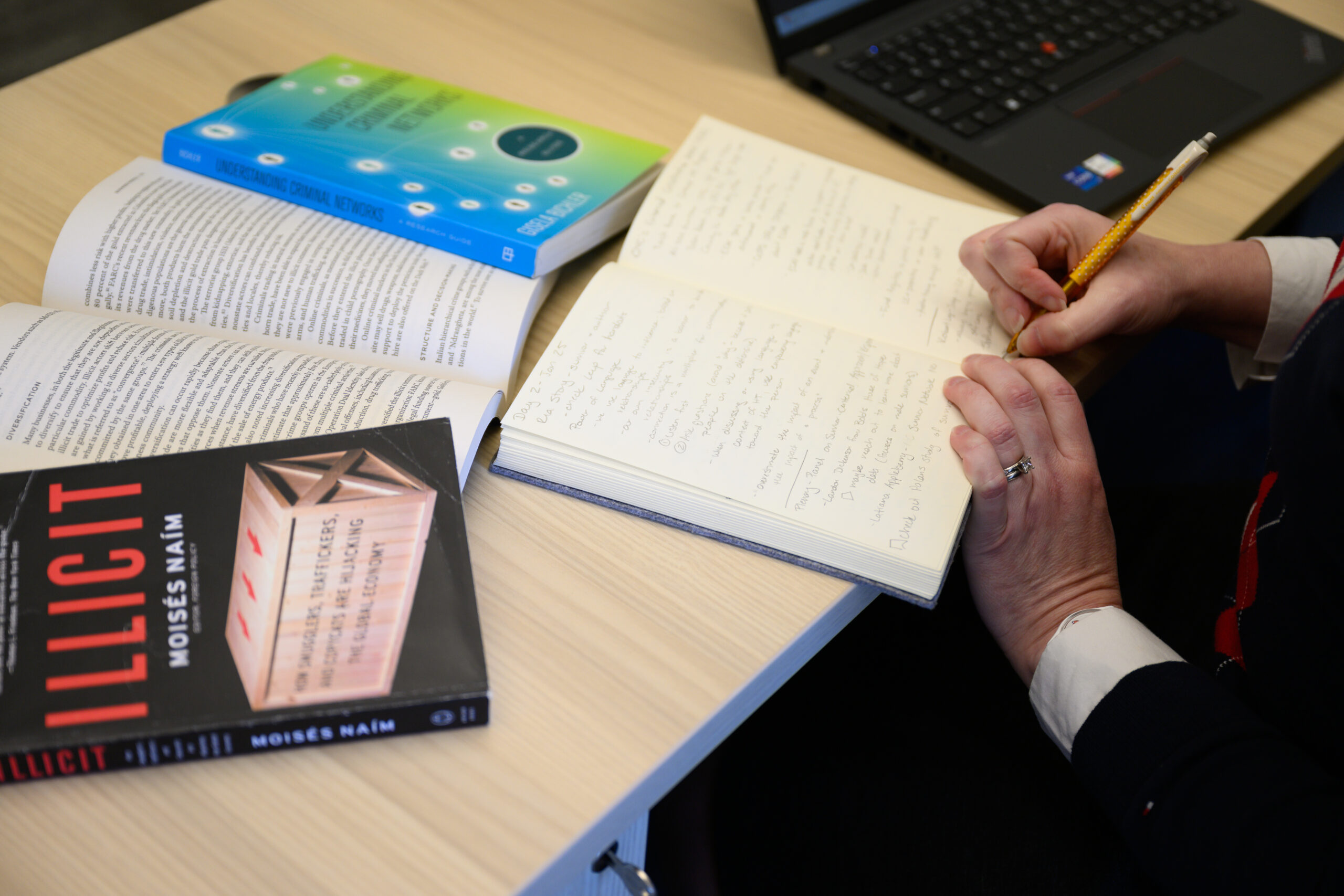

Petter, the inaugural associate provost for faculty affairs and the Peter C. Brockway Chair of Strategic Management in the School of Business at Wake Forest University, has devoted her research and scholarship to detect and disrupt human trafficking and other illicit activity.

Supported by a $1 million grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) awarded in January 2024, Petter and three research partners – Gisela Bichler, a criminologist from California State University, San Bernardino; Felipe Aros-Vera, an engineer from Ohio University; and Yan Zhang, a computer scientist from California State University, San Bernardino – will spend three years working to understand illicit decision making within supply networks.

“We’re trying to understand illicit decision making and the decisions that enable illicit activity to happen,” explained Petter. “Human trafficking is one form of illicit decision making, but there’s a lot of other types of criminal activity that can create harm in society.”

Each year, human trafficking generates “more than $150 billion in illegal profits across the globe.”1 And for the most part, it is a crime that hides in the shadows, making it difficult to know how many people are harmed. According to the U.S. Department of State, there are an estimated 27.6 million victims of human trafficking worldwide.2 The North Carolina Department of Administration reports that “human trafficking is one of the fastest growing crimes in the United States with North Carolina among the most affected states.”3 In fact, “North Carolina consistently ranks within the top 10 states for human trafficking.”4

Now, someone who thought she was going to be a second grade teacher is spending her days trudging through those shadows trying to frustrate and disrupt human traffickers.

Petter’s journey started with the idea that she wanted to teach. Then science captured her imagination and curiosity drove her into the realm of computer science. She earned her MBA at night while developing software. She ultimately earned her doctorate in computer information systems from Georgia State investing her research efforts into how to evaluate information systems to know if they are successful, how they could be improved, and how to assess them from various perspectives.

That initial calling to the classroom led her to her first job as an assistant professor at the University of Nebraska Omaha. There, Petter led a program to help promote more women in the male-dominated fields of computer science and information systems. Through that program, Petter connected with a librarian who was doing work in human trafficking. Knowing that human trafficking can happen domestically or internationally and that it may or may not transcend borders, the librarian asked Petter if some of the women studying information technology could help build software to track migration paths that may occur in international human trafficking.

“Women tend to go into technical fields because they want to make a difference,” said Petter. “This project idea helped me learn more about human trafficking. The seed was planted.”

Her next stop was at Baylor University in Waco, Texas. After she learned about human trafficking occurring in her community, Petter reached out to a local nonprofit organization working to curtail the effects of human trafficking to see if she could help. As it turned out, they needed some researchers, so Petter lent her expertise where she could.

Soon after, at an academic conference, she struck up a conversation with Laurie Giddens, a doctoral student who was pursuing her PhD in information systems at Baylor. Through that discussion, Petter and Giddens realized they shared an interest in curtailing human trafficking.

“This is not normal tabletop conversation,” admitted Petter.

While they shared a common interest, it would take a few years before their collaboration took off.

Petter had long been trying to link her personal interest and growing passion for making a difference in society with the research and teaching components of her career. A phone call from Giddens suddenly connected Petter’s two worlds, and the scholars started a collaboration with a nonprofit focused on using technology to identify human trafficking activity. Their goal was to help the nonprofit enhance its already existing technology.

One key part of their work was attending in-person training sessions to understand how law enforcement used technology. That curiosity led to developing a pitch to the National Science Foundation (NSF) to support their work to better understand the complexity of human trafficking.

“I view the world through a systems approach – technology and business focus, but there are many other pieces of this puzzle.”

“There’s a criminal justice aspect, an economic aspect, a political science component that deals with policy. There are practitioners that bring different pieces to the table. There are nonprofits who work with victims that can give other insights.”

The NSF grant provided an opportunity for Petter and Giddens to bring all of those disparate players to the table to better understand the role of technology in human trafficking by gathering information from dozens of people who approach the issue wearing different lenses.

They asked questions like: How are law enforcement and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) using technology? What are the barriers to using technology effectively? How are criminals using technology to advance their purposes?

In understanding the bigger picture, they could better address the problem.

Petter found her way to Wake Forest in 2022, a natural home for one who wants to teach and pursue their scholarship. With her, came her work which allows her to use her talents for the good of humanity.

“As someone who focuses on business, I can think about the criminal enterprise as a business,” said Petter. “I can transfer all of those things that a small business might do with technology to an individual or organization exploiting people through human trafficking. I can understand how their business works and can look for ways to break it down. Typically, you want to help businesses thrive and be resilient. This is a case where we don’t want them to be resilient. We want these businesses to break.”

The latest NSF grant awarded in August 2023 will advance Petter and the team’s work on understanding illicit decision making by focusing on a few different components.

First, they will start by investigating the massage therapy industry. While many business owners are engaging in fully legitimate business activities, it can also be an industry that is fraught with illicit activity – including paying employees under the table to avoid taxes, requiring kickbacks, laundering money, or engaging in human trafficking.

“The challenge is that we can’t study this in a traditional way.”

“I can’t go interview people about their illicit business activities. I can’t ask someone why they made the choice to pay someone under the table or why they are allowing their massage therapists to engage in commercial sex for tips. We have to go about getting insights in a different way by making assumptions and running experiments. So, we’re using agent-based modeling, or a form of simulation.”

That kind of simulation was made more mainstream during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the world became familiar with contagion models that illustrated the exposure of people to the virus and the rate of infection. It helped visualize how the virus spread and permeated over time. Using a similar approach, Petter and her team are trying to build a model that investigates the massage therapy industry, the network of owners, and the connections that extend outside the network.

For example, imagine that one owner of a massage parlor decides to choose to do something illegal. How does that affect the other people in that owner’s network? Do his connections begin engaging in that same behavior and making those same illegal choices?

Petter and her team wondered what would happen if there were certain disruptions to the operation. What if more oversight was implemented in this industry? How do policies or regulations change the behavior of the owners? Do these policies or oversights lead to less illicit decision making? Is that policy more or less effective than a law enforcement agent driving by periodically?

“We can run all of these experiments, trying to figure out – based on probability, industry data and certain assumptions – what might be the most effective way to try to constrain illicit decision making,” said Petter.

“Perhaps we could introduce some friction in the process and make it more difficult or risky to make an illicit decision and nudge them in the more legitimate direction.”

Once the model is created and refined, Petter and her team want to develop a way to apply the process and principles to constrain illicit decision making in other industries.

“Think about agriculture – where there can be illicit activity like paying people under the table or hiring undocumented workers,” Petter said. “Further extensions of illicit activity could include labor trafficking. What factors of that industry lead people to engage in illicit decision making? Think about pharmaceuticals. You can have counterfeit pharmaceuticals or smuggled pharmaceuticals. What about wildlife trafficking? Let’s transfer the ideas of the model and apply it to any type of illicit activity to figure out the types of interventions that are most likely to be successful.”

By changing parameters to the model, the research Petter and her team are doing could influence any number of areas in society where illicit activity is thriving. And ultimately, they can reduce harm to human beings.

Another component of the work includes students. Petter and her team across the country will be shaping two collaborative classes for students from their respective institutions. The first course will invite students to determine other industries where a model of this type could be applied and develop the parameters that need to be adjusted for the model to have success. The professors will run the model in those particular industries, and another semester’s class of students will help interpret the results of the study. The researchers would then digest all of the work and develop practical implications in real world contexts.

“I want to understand the most proactive approach to combating illicit activity,” said Petter. “There is a lot of effort that might help in the short term, but it is not helping the bigger picture of the problem. How do we get from addressing the symptoms to responding comprehensively to this important issue that needs to be addressed? How do we think systematically? Can we look at the bigger picture? How do we channel the energy in a way that is productive in creating a solution?

“My goal is to have more insight and recognize we all have a role. There are ways to better identify or constrain the activity.”

“We’ve got to bring all of the pieces together or we’re never going to make any progress on this. If we can do anything that starts to move the needle, that’s a win.”

Petter and her team are well on their way. Not only are they working to combat a major societal problem, they’re inspiring and teaching the next generation to do the same.

Dr. Stacie Petter serves as the associate provost for faculty affairs and professor in the School of Business. As the inaugural associate provost for faculty affairs, Petter is responsible for faculty development initiatives and resources, recruiting and evaluation policies, faculty funding programs, faculty recognition programs, and many more areas impacting the faculty experience. She joined Wake Forest University in 2022 as a professor of management information systems and served as the area chair for analytics, information systems, marketing, and operations management. In 2024, she was named the Peter C. Brockway Chair of Strategic Management.

- https://cosspp.fsu.edu/why-human-trafficking-is-more-than-just-a-moral-issue%EF%BF%BC/#:~:text=Human%20trafficking%20also%20carries%20heavy,true%20value%20of%20human%20trafficking ↩︎

- https://www.state.gov/humantrafficking-about-human-trafficking/#human_trafficking_U_S ↩︎

- https://www.doa.nc.gov/divisions/council-women-youth/human-trafficking/basics#HumanTraffickinginNorthCarolina-6902 ↩︎

- https://www.nccourts.gov/assets/documents/publications/HTC-FactSheet-2022-23.pdf?VersionId=hOr8Qmv5FCzTM6hsQEhiWu5RKldiEIAD ↩︎